Afrofuturism, Cyberpunk, and Video Games

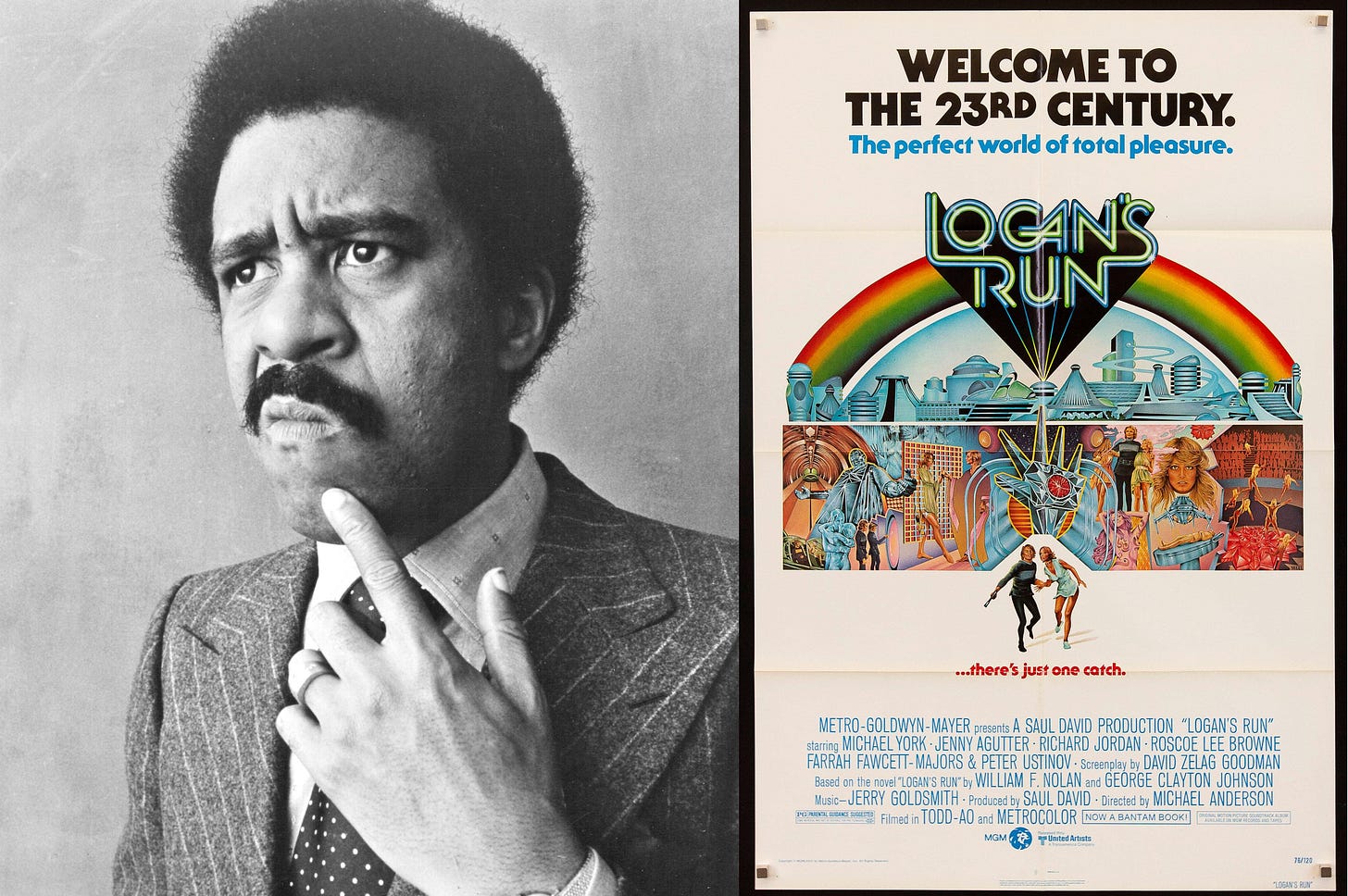

African American comedian Richard Pryor once famously spoke of Logan’s Run (1976), a science fiction movie. He noted that in the 23rd century of the film’s narrative, there were no Black characters: “Guess they’re not planning for us to be around. That’s why we gotta make our own movies.” As an African American, Richard Pryor noticed something that a lot of people didn’t; science fiction movies didn’t have Black people in them. There were indeed no Black actors on screen in Logan’s Run, but Roscoe Lee Browne was the voice of the robot Box in the film. So there was a Black person there, they just weren’t visible. They were represented, just not visibly. Richard Pryor‘s observation serves as a useful metaphor for the subject of Black contributions to video games; representation, or our vision of reality, doesn’t always match with actual reality. Sometimes there are people we don’t know about who make very important contributions to things we engage with. Sometimes they’re underrepresented, sometimes they’re poorly represented, and sometimes they’re not represented at all. That doesn’t mean they’re not there.

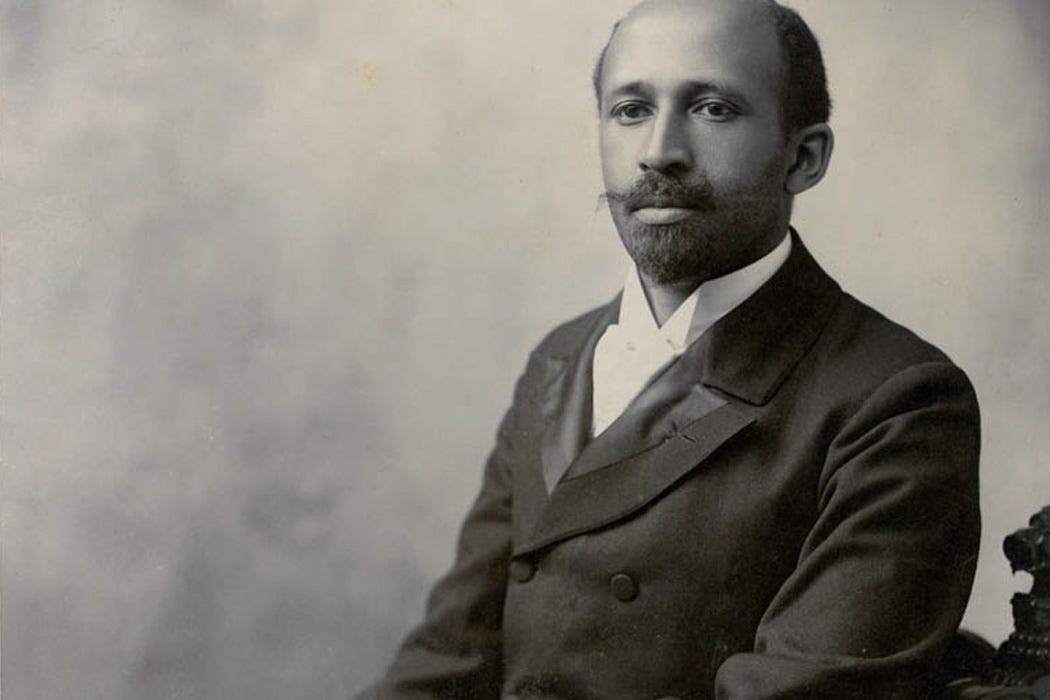

WEB Dubois

WEB Dubois was the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard. He was a historian, a sociologist, and a prolific author about civil rights in America. He also wrote “The Comet,” a 1920 short story that is one of the earliest examples of American Science Fiction. For context, 1920 is also the year that Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Frank Herbert were born. Other African American science fiction writers include Octavia E. Butler, Tananarive Due, Minister Faust, Andrea Hairston, Nalo Hopkinson, N. K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and Nisi Shawl. I list them here in case you wanted to find out more about them or read their works. Another African American science fiction author is especially important for video games.

Samuel R. Delany was born in Harlem, New York, in 1942. By the time he was 20 years old he was a published author; The Jewels of Aptor, written when he was 19, was published in 1962. Delany gained prominence in the Science Fiction literary field in the 1960s. He is the author of 1968’s Nova. The main character, Lorq, is ‘Afropean’; his father is Norwegian and his mother Senegalese. When Nova was first completed, Delany submitted it for potential serialization in Analog, one of the popular science fiction magazines of the time. Serialization would have exponentially increased the novel’s exposure, increasing its chances of competing for or winning the Hugo Award, the most prestigious award in science fiction literature. The editor of Analog told Delany’s agent that he wasn’t sure his readers would find a Black protagonist relatable. The same editor allegedly told author Dean Koontz that the idea of a technologically advanced Black civilization was “ a social and a biological impossibility.”

Samuel Delany, 1968

The Analog editor cited the ethnicity of Nova’s protagonist as virtually the only reason for rejecting serialization. But given the time an place in which the novel was created, and who it was created by, Lorq’s ethnicity is absolutely relevant to all of the other dynamics in the novel: technologically altered humans, disillusionment with oppressive societies, and the tension between homogenizing ‘progress’ and artistic, individual expression. In the 1960s African American civil rights was a prevalent social issue. At that time, Science Fiction writers (and readers) were almost exclusively white men. The editor’s blithe dismissal of the novel ironically validates the novel’s themes of social disillusionment and an oppressive environment as well as the relevance of the protagonist’s ethnicity.

In media like films and books, and especially in video games, there exist spaces that aren’t real but still constitute worlds. In science fiction, ‘the future’ is a place where space travel, aliens, and incredibly advanced technology exist. When we interact with movies or books or games set in the future, we make allowances for things we know aren’t real in the present. At the same time, the people that produce or distribute those stories (or build us those games) are making choices about what is or isn’t in the narrative. More importantly, they make choices about who is and isn’t in them. Science Fiction as a genre is wholly based on things that are social and/or biological impossibilities; it’s not logical to say that a specific group of people is incapable of participating. The Analog editor may not have thought it was possible, but other people certainly did. Marvel Comics’ Black Panther character, and his home nation Wakanda, first appeared in 1966, two years before Nova was released.

Science fiction lends itself to visual media like film and, of course, video games. It’s a genre that involves, and more importantly can inspire, a great deal of imagination for both its creators and its consumers. In the 1970s and 80s, before video games became capable of the immersion and graphics we now might take for granted, the only way to participate in a science-fiction based narrative was to imagine yourself doing it. Luckily, there were people willing to help structure and codify that experience. Role playing games were introduced to the world in 1974 with the release of Dungeons and Dragons. There were rules, and a ‘dungeon master’ who rolled the dice and described what the players were seeing and experiencing, but all of the players (and the dungeon master) imagined it differently. The tabletop RPG genre grew popular in the years before video games could offer visually engaging alternatives, and even now they still have a dedicated fanbase.

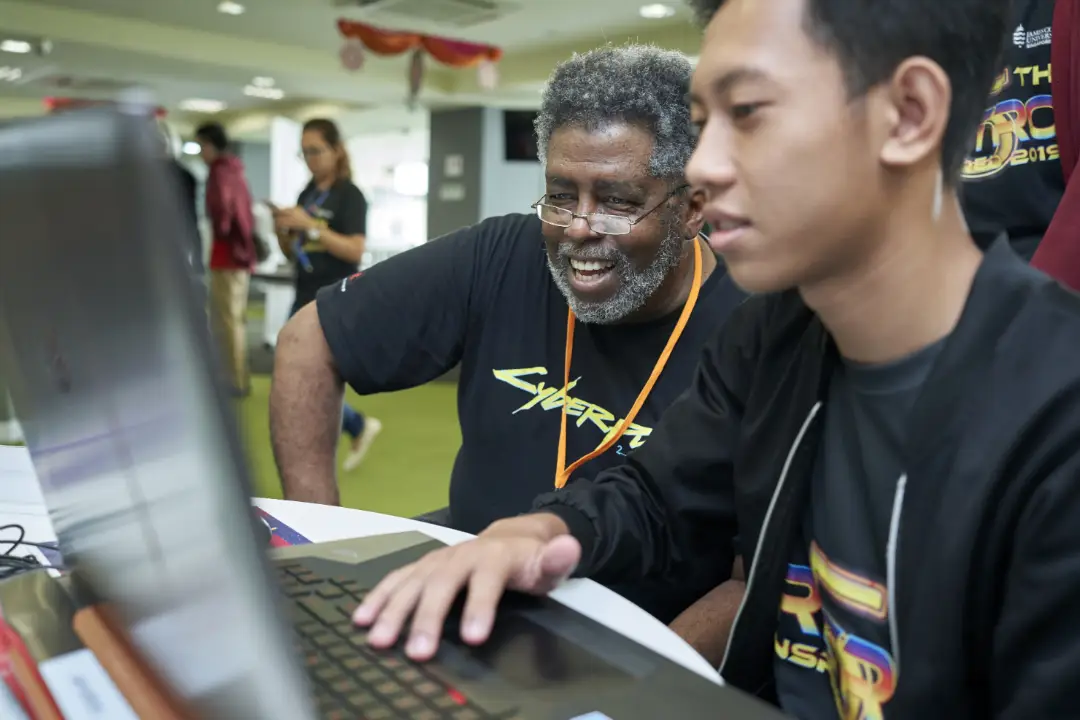

Mike Pondsmith

Mike Pondsmith loved playing games as a kid. He also enjoyed designing them as a kid. He was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons while studying at UC Davis. He was intrigued by the mechanics and structure of D&D, but not so enamored of the setting. He enjoyed Traveller (1977), a science fiction RPG by Game Designers Workshop, much more. He liked the setting enough to rework the game mechanics to his liking, creating Imperial Star. Developed for his personal use, the game was exactly what Pondsmith wanted. He worked in the early game industry bringing Japanese video games into the American market. But he kept working on RPGs and found success with Mechton, an RPG based on Japanese mecha anime. This success convinced him to start R. Talsorian Games (RTG) in 1982.

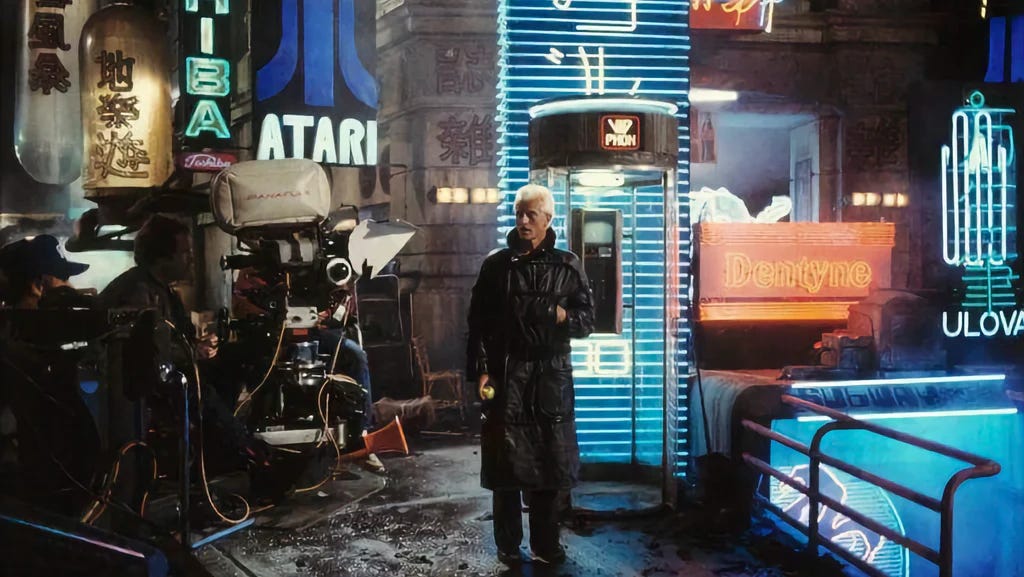

We don’t hear the word ‘cyborg’ much any more; it’s a portmanteau of cybernetic and organism, but at one time it was common. Cyborgs were forerunners of cyberpunk’s human-machine hybrids. The word ‘cyberpunk’ was coined in 1980 when Bruce Bethke used it as the title of a science fiction short story. It was popularized through frequent use by editor Gardner Dozois of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine. Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner (1982) introduced what would become the visual aesthetic of cyberpunk: neon shrouded in pollution, advanced technology and urban blight, physical enhancement and moral decay. The film also includes an inadvertent example of how wrongly we can imagine the future; the Atari logo appears more than once in the film, which is set in the then-future 2019. Atari ceased to exist in 1999.

In 1984 William Gibson’s Neuromancer, popularly held as the first cyberpunk novel, was released. Gibson acknowledges Samuel Delany’s Nova as a major influence on his own novel. In 1988, Mike Pondsmith and RTG released Cyberpunk, a tabletop RPG set in a dystopian future. It spawned a franchise as well as CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077, a sprawling open world RPG that tried to remain as faithful as possible to Pondsmith’s vision of cyberpunk.

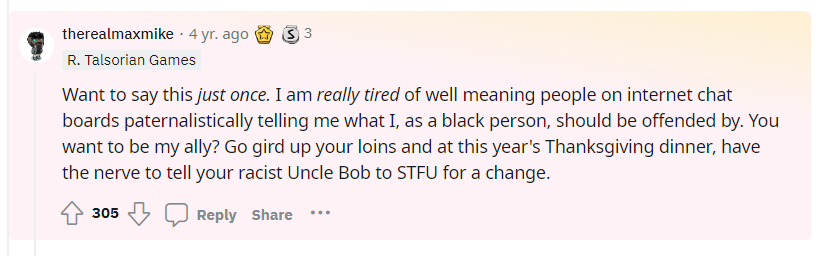

Cyberpunk 2077 was one of the most anticipated video games in recent history. CD Projekt Red had found great success with The Witcher 3, and hoped to push the envelope even further with their next release. Working with Mike Pondsith, the developers created a vast open space populated by NPCs who were technologically enhanced. The player controls their own enhancement through a complex system of upgrades. Upon release, the game garnered as much attention for its flaws as its weaknesses; bugs made the game unplayable for some, and the process for refunding the game was initially nonexistent. Even before the game’s release, objections were raised about the representations in the game. Ethnic minorities in the game were seen by some as being reduced to stereotypes. Pondsmith responded to these criticisms quickly and pointedly: "Who the (bleep) do YOU think you are to tell ME whether or not MY creation was done right or not?"

Pondsmith’s replies illustrate the ongoing difficulty of being a Black creator in an overwhelmingly white space. Like Samuel Delany, he is forced to defend his vision, and his work in ways that other creators do not. Both creators are forced to advocate not just for their culture but for the ability to portray it in the face of cultural outsiders attempting to tell them who they really are or should be. Even if Pondsmith’s characterizations are imperfect, he at least has creative control over them. Pondsmith’s position as one of the founders of the cyberpunk genre means he is both capable and entitled to create a world of his choosing. He is also claiming the space and right to make those characterizations as someone who has experienced what it’s like to have others tell you what you can or should be.

Cyberpunk is grounded in the idea that the future won’t bring equality or equal benefit; some people will live and thrive in the future while others will not. If this sounds familiar, it should; it’s the same thing Richard Pryor was talking about. Cyberpunk can be seen not just as a metaphor but an actual manifestation of America’s refusal to grapple with issues of race. The cyberpunk vision of the future is a collision of ‘lowlife and high tech,’ of advancement for some and stasis (or regression) for others. The dichotomy of coexisting advancement and atavism provide the central tension of cyberpunk as an aesthetic, a genre, and an idea; in the future, technology will be better but society will be worse. People will be physically more advanced, but moral conditions will either stagnate or worsen. This idea, that technology and time will be of benefit only to some, has obvious relevance to the present day.

Sun Ra

While some were certain that people of African descent had no place in an imagined future, others were hypothesizing differently. Sun Ra, born Herman Poole Blount in 1914, was a jazz composer and keyboardist who led an ever-changing music ensemble called The Arkestra. Sun Ra claimed to be from Saturn, on Earth only to spread a message of peace through music. The Arkestra’s elaborate stage shows featured a mixture of ancient Egyptian motifs with Space Age elements. In 1971 he taught The Black Man in the Cosmos at UC Berkeley as an artist-in-residence. The following year he wrote and starred in Space is the Place, a feature film about an attempt to make a distant planet a home for African Americans. Sun Ra, Samuel Delany, and Octavia Butler are considered the first Afrofuturists.

Afrofuturism is a school of thought in academia and science fiction that is centered in African cultures. Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture, calls it a "cultural and artistic practice that goes back to ancient African griot traditions and Egyptian astronomy… the intersection between Black culture, technology, liberation, and the imagination, with some mysticism thrown in, too." Afrofuturism takes an interest in representations of people of African descent in the context of how we think about and imagine the future. Critics of Afrofuturism ask why it is necessary to center Black history and culture in hypothesizing the future. Yet they do so while often ignoring or denying the fact that popular conceptions of the future have self-evidently been centering White culture, as the Analog editor did. Afrofuturists understand that ethnicity has relevance and importance both today and in the future. Some Afrofuturists assert that cyberpunk is Afrofuturism; look at who helped create and popularize it. It is only logical to wonder how and why the designers’ lived experiences may have influenced their creations. Conversely, we aren’t always aware of the people who helped create things that are part of our lives.

You may be familiar with the words ‘Otaku’ or ‘geek.’ We have preconceptions about what they look like in human terms. But it is unlikely that you picture someone of African descent when you hear those words. Blerd is a portmanteau, short for Black nerd. It highlights yet again the ways in which many of us can be surprised by something, or someone, we didn’t realize existed. It also highlights the desire for some to stake out a space in which they may not be noticed or included. But like Samuel Delany’s experience with Analog’s editor, the utility of Blerd is much more about exterior perceptions than interior ones. Yet the term itself is contentious. Reynaldo Anderson is a leading Afrofutirist scholar who finds the term problematic, self- limiting, and feels no connection to it. “I never connected with it. Its an insulting term to me. A lot of the energy that led to our influence on the contemporary Afrofuturism movement came from our exposure to anime like Ultraman and Speed Racer, comics, and Pong as 70s kids in elementary school. In a lot of ways the 70s was a much more open and freer culture than now. More experimentation. Blerd is pretty much a branding phenomenon.”

Like Sun Ra, the rock group Living Colour sought to bring music into the future while remaining grounded in and acknowledging the past. Both Sun Ra and Living Colour are part of the Afrofuturism exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The band was formed in 1984 by guitarist Vernon Reid, who is also a dedicated science fiction fan and self-confessed Blerd.

Living Colour is best known for “Cult of Personality,” a song used in film soundtracks as well as video games, including Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and Guitar Hero III. The song has cemented a place in the pop culture landscape; its opening riff is instantly recognizable. The band, however, is less so; even today, not everyone is aware that all of Living Colour are African Americans. That example is relevant to Black games and Black game designers because it happens more often than we might like to acknowledge; we don’t know, or don’t see, the people who create things we engage with.

We Are the Caretakers

Afrofuturism is moving beyond literature and film, becoming its own game genre. Heart Shaped Games has developed We Are the Caretakers, a squad management RPG. The game involves defending Raun, large creatures that resemble rhinos, from poachers both human and alien. Instead of playing a tourist or game warden, the player is someone who lives in the game world in an attempt to help players understand and appreciate what it is like for those in the real world who live similarly; morality can sometimes take second place to survival for some people. HSG’s founder Scott Brodie sees Afrofuturism as “a way to center stories around Black people and the broader diaspora and not being so Western-centric. I was first introduced to it through Black Panther… we ultimately saw that there is a non-Western story here that we could tell, and Afrofuturism really fit what we wanted to try to do.” Narrative designer Xalavier Nelson also credits Afrofuturism with informing both the game as well as his own worldview. “Here we are making this Afrofuturist game, and I’m finding myself, despite the incredible art of the game, uncomfortable for some reason. And it wasn’t until I was on a plane watching Black Panther that I realized, oh, the reason I’m deeply uncomfortable with the representations that I’m seeing is because every other time that I’ve seen explicitly joyous Africans in culture and cultural influences … it’s been as a joke. It’s been a punch line in a comedy at some point. It’s been some sort of thing to make me feel less than.” He found working on We Are the Caretakers a deeply personal experience because of “the ability to invest in characters that look like me or that bore elements of my heritage…To love this world I had to learn to love myself.”

A literally Afrofuturist game was produced by Kenyan game studio Jiwe. 2021’s Usoni means future in Swahili, the most common language in East Africa. In 2063 two people journey from a decimated Europe towards Lake Turkana in Africa, the only place left on Earth where there is still sunlight. The game is based on a novel by Marc Rigaudis, who had filmed a pilot episode for a potential series. He was contacted by production companies interested in the project, but “When I said I wanted this production to be made in Africa, they usually lost interest.” Instead, Rigaudis decided to turn the novel into a video game. Rigaudis’ former colleague Max Musau had started Decoded, a game studio. “The goal was to bring tech communities together and lower the barrier to learning technology and code. We also started organizing esports competitions, and we were thinking about creating video games. In June 2020, I remembered the Usoni story when I randomly met Mark at the supermarket. The minute I saw him I thought, ‘If I want to make a game, this would be the first place to start!’”

Black game creators, like Samuel Delany and Mike Pondsmith before them, are burdened with expectations and limitations that their non-Black peers are free from. Black game developers are asked how and why their game has any market appeal outside of their race, a question the developers of Pressure Washer Simulator likely never faced. Few games feature Black (or female) main characters because players ‘may not like it’; EA Sports’ FIFA 17 featured a story mode in which the main character’s one unchangeable characteristic was beingBlack; some players complained. That same year, many people had no problem playing as a blue hedgehog named Sonic.

Because video games spent several decades not having non-white protagonists, developers now say that players don’t want them, or that it is too great a financial risk to attempt. It may also be an issue of not knowing or caring about certain segments of the market. Latoya Peterson of Glow UP Games was involved in developing a game based on the hit HBO show Insecure. The show’s success, however, didn’t mean that funding for the game would come easily; investors weren’t confident that a game with a Black female protagonist would have broad appeal. “We were told there was no data to justify it…They told us they don’t know how many BIPOC people are playing, particularly how many Black women are playing.” Sugar Games founder Keisha Howard puts it more bluntly: “There is power in diversity. But nobody gives a fuck unless I can substantiate it in a million different ways.”

For Dr. Katryna Starks, “The absence of Black characters in games is a very serious problem…Black kids aren’t seeing themselves as the heroes, they aren’t seeing themselves solving the problems and wearing the capes. We deserve to feel that these gaming worlds were made for us to be in, too, and that we belong there.” Recent surveys of the video game industry show that African Americans, who make up 13% of the US population, make up 11% of gamers. The lack of representation in games is mirrored by the lack of representation in game development.

African Americans are the third largest gaming demographic (after Caucasian and Asian Americans), but they make up only 3-5% of game developers, 80% of whom identify as Caucasian. This can make it difficult for young Black game designers to feel included. Developer Charles McGregor, founder of Tribe Games, says he only began to feel as if he belonged when he "went to more industry events where I started to see other Black people." It was only in experiencing it that he realized how important it was. "When you are immersed in an environment where you're no longer the minority person, that is something that it feels like you're breathing a sigh of relief. You're able to talk about things and relate to people."

Fellow developer Neil Jones experienced similar challenges in his own career. “I was giving up on the game industry because I really couldn’t find an opportunity,” he said. “I spent almost 10 years applying for jobs. The game industry has historically had a type, and I didn’t fit the mold of what they thought a game developer looked like. So I decided to make a game on my own.” Jones credits the Black gaming community for the support and encouragement he needed. “There are so many Black gaming groups who look out for Black folks in the industry. They always supported me and rallied around me, and it made me feel like the game could be something.” He feels, however, that the disparities in game development will likely continue, precisely because of the past: "I don't think we'll ever be able to fix the original sin of these massive studios who have hired people over the last 20 years actively not hiring Black people. We can never make up for the lost time."