Money Can’t Buy Happiness, but It Can Pay for Therapy

I lived and worked in Hong Kong for nearly two decades. I never thought of myself as a ‘good’ expat as much as I was constantly shocked by how little it took to make a positive impression. I was in a 7-11 in Tsing Yi MTR once, and said ‘thank you’ in Cantonese [m'goi sai] when the cashier gave me my change. Her eyes grew wide, and she said “Wow, you speak Cantonese.” In Cantonese. She was shocked, but so was I. If knowing how to say ‘thank you’ in the local language is impressive, the standard is obviously very, very low. Logically, that meant a lot of expats did virtually nothing to adapt to their environment. If you don’t believe me, watch Expats.

A scene in the series, featured in the trailer, shows Nicole Kidman dancing in a small noodle restaurant to Blondie’s “Heart of Glass.” I spent the vast majority of my time in Kowloon and the New Territories, places these characters have little to no experience with. In the Hong Kong I lived in, any white woman meretriciously dancing and singing in a restaurant would unceremoniously be told to shut up, pay the bill, and get the f@#$ out (“收聲死鬼婆!收錢,走撚去!”), and deservedly so.

The scene is a painfully obvious and cringe-inducing ‘homage’ to Wong Kar Wai. In the third episode, just in case we didn’t know that was an homage, there are people name-checking the director in background dialog. But they are doing so in English, which at least lends an air of verisimilitude. Most of Wong Kar Wai’s films weren’t popular in the city whose essence so many Westerners breathlessly assure us Wong captures. No one in Hong Kong, myself included, wanted to spend two hours watching Tony Leung Chiu Wai silently pondering the meaning of life while smoking an entire cigarette. On the other hand, European and American art house viewers reveled in it.

Wong Kar Wai freely admits to creating what little story there is in his films not during shooting but in the editing process. As a consequence, his films are very open to interpretation; it’s possible to make your own meaning, because little to none is presented in the film itself. This naturally may lead to viewers flattering themselves by thinking they understand something that not many people do, condescendingly thinking, or even saying, that people critical of the films “don’t get it,” but of course they do. Egotism looms large in both the production and consumption of so-called ‘art.’ There’s an inherently egotistical aspect to expecting an audience’s attention across several hours, or of content being unquestionably entitled to such attention because of some ephemeral value it supposedly holds. In that sense, Expats succeeds as an homage to Wong’s filmmaking.

The series is riddled with that same sense of patronizing entitlement, both by its characters as well as producers. Much like Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, Expats expects us to care about and empathize with characters who show virtually no willingness to do so with the people or city around them. We are further expected to indulge filmmakers who, like their characters, think we won’t notice or question their privilege.

Expats wants, or demands, that we empathize with people we may have lived in proximity to, but never with. The audience is expected to lavish them with attention and empathy because the characters’ monolithic self-absorption tells them so. They’re them, after all, and don’t we know who they are? The characters in Expats are somehow entitled to our attention, and they’re entitled to expecting our attention. But given who these people are, it’s not really a surprise. Expats focuses on one of Hong Kong’s smallest, wealthiest, and most entitled communities, and it is also one of the city’s most isolated. You can see the Peak from almost anywhere in Hong Kong, depending on the air pollution. But unless you’re born into a very exclusive club, you’re only ever going to visit. The rest of the city doesn’t resent these people’s isolation; they’re grateful for it, because that way they don’t have to deal with these awful people. Except in the odd late night noodle restaurant…

Expats never seems to expend any time or energy explaining why the audience should have any sympathy for characters who, intentionally or not, illustrate the veracity of the term ‘filthy rich.’ The show also never seems to tell us that these self-evidently loathsome people are anything but normal. It simply assumes we can and should empathize with these monsters. The solipsistic suffering of the main cast of Expats is a fascinating aspect of the show, if only because it assumes itself and its cast to be of interest to anyone. The only people who don’t know the rich lead vacuous, uninteresting, empty lives are apparently the rich themselves. And even when they realize it, somehow it becomes everyone else’s responsibility to fix or reassure them; after all, isn’t servitude what the non-rich exist for? The rich are apparently too busy not raising their children, or expecting the help to do it, only to resent the children preferring the helper to them. Nancy Kissel may have been a homicidal maniac and crazier than a bag of rats, but at least she had the common decency to kill her husband before cartoonishly expecting sympathy. Unlike the dry husks in Expats, Nancy did something before grossly indulging in entitlement.

Expats is based on The Expatriates, a 2006 novel written by Janice YK Lee, a Korean American who was born in HK, something we have been repeatedly told. We are less often reminded that she attended the Hong Kong International School and graduated from Harvard. She returned to Hong Kong in 2005 as a wife and mother, having married Joseph Bae, co-CEO of American global investment company KKR. Lee vociferously denies writing about any of her friends in a profile published in Tatler Asia. They are, after all, wealthy enough to afford legal representation. Lee claims the idea for the novel began simply as a vision of a woman frozen in apprehension over a dinner party she was to host: “I didn’t know who she was, what ethnicity she was, where she lived-I didn’t know anything.” For someone who claims experiential knowledge of living in Hong Kong, that’s an odd assertion, because that image in fact allows anyone who has lived in Hong Kong to know quite a bit about who and what these people are.

They’re people who mistake their disposable lives for profound Greek tragedies, who are so blind to their own privilege and status that they are devoid of humanity. Mercy, a young Korean American, has fled New York (and her mother’s nagging) to Hong Kong, to ‘find herself’ after graduating from Columbia. This kind of suffering is somehow worthy of attention simply by virtue of its occurrence. She works a number of menial jobs while wearing an expression we are expected to interpret as reflective of her inner despair. In Hong Kong, 20% of the people live in poverty, and the city’s income disparity is at its highest point in decades. But we’re expected to reserve special empathy for an Ivy League graduate who chose to run away from her mother via an intercontinental flight. That’s real suffering, apparently. Mercy doesn’t speak Cantonese, which in reality would preclude her from the vast majority of the jobs she is shown working. If anything, Cantonese is used as some sort of audio cue for her isolation and emotional desolation. Why won’t Hong Kong make a place for someone who doesn’t speak the city’s language and shows no interest in the city or anyone in it (except herself)? Life is so unfair. But Mercy is not alone in her solipsism.

Expats itself shows no interest in the city or culture that these characters live next to. I refuse to say they live in it, because they don’t. We may recognize the Hong Kong of Expats, but we will also recognize it as an incredibly shallow, expat-centric version of the city. The word ‘Kowloon’ is used in the same way that 19th century British authors intoned ‘Africa,’ a place of ever-present menace mixed with a frisson of irresistibly exotic attraction. The Fa Yuen street market can seem menacing only if looked at from a place of abject ignorance. Or a balcony on the Peak. In Expats, the city exists purely as a visually interesting backdrop for these desiccated, empty characters to wallow in their self-pity and entitlement, wondering why seven million people aren’t helping them. One of Mercy’s new local acquaintances is shocked to discover that the TV show Friends wasn’t actually filmed in New York. I doubt there was any self-awareness of Expats doing essentially the same thing. There is plenty of evidence to the contrary. The book, like the series, focuses on Mercy, the youngest of the three protagonists by far. Any 100-level Psychology course would tell you that a novel written by a middle-aged woman whose story is centered on a promiscuous character of the same ethnicity but half the author’s age is blatant wish fulfillment. Sadly, the entire series is just as transparent, pedestrian, and lifeless. The only thing interesting about it is its checkered production history.

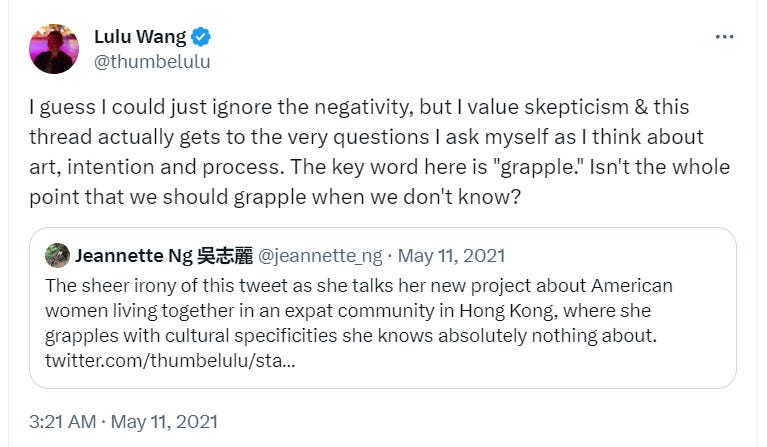

In 2020, director Lulu Wang took umbrage with Ron Howard’s selection to direct a film about Chinese pianist Lang Lang, saying it would require “grappling with the cultural specificities of Northeast China,” where Wang is from. She felt that Howard, not being from the same place, was unqualified to tell the story. Howard, who directed Apollo 13, isn’t an astronaut either. He’s not even a rocket scientist. Neither is Lulu Wang. Somehow it wasn’t a problem for an Asian American director born into a Red family that immigrated to the US at age six to tell a story set in Hong Kong. Wang deflected such criticisms by saying that grappling with the unknown is part of the work, an indulgence she did not extend to Ron Howard.

Part of grappling with the unknown for Wang would have been the language divide. Wang speaks Mandarin, but not Cantonese. According to an article in the LA Times, in Hong Kong “Wang is an American, an outsider, but she’s still privy to the conversations around her as a native Mandarin speaker, an insider.” Considering that Cantonese is still the most widely spoken Chinese language in the city, those conversations are actually the least likely to be local. In a recent social media post, Lulu Wang claimed “Cantonese is a dying language which is why it’s important to speak it, hear it, defend it… But when I was in HK, there was an overwhelming amount of Mandarin (on subways and other public announcements)… and that speaks volumes.”

It does indeed speak volumes, but Wang is either unable or unwilling to listen to them. Had she made even a cursory attempt at grappling with the city’s realities, she would know that the ‘overwhelming’ proliferation of Mandarin is just one of the many ways the Hong Kong government has participated in the city’s integration into what is called the Greater Bay Area, an assimilation designed at least in part to erase the city’s uniqueness and bring it back into the fold of the motherland. Cantonese is spoken by over 20 million people, but in China it, like many other languages, is being marginalized. Cantonese isn’t dying; it would be more accurate to say it is being murdered, much like the city where most people speak it.

But accuracy is plainly not a concern for the director or the series. Like many of her contemporaries, and her characters, Wang speaks with what might be called a “Hollywood accent,” where so much of what is said is transparently disingenuous, fatuous, and trite, but is simultaneously expected to be taken seriously. An old aphorism reminds us to never let the truth get in the way of a good story, and Lulu Wang took that to heart. While filming the series, she posted on Twitter about a miraculously serendipitous event:

The two fictional young women live in a city that is home to Ann Hui, Sylvia Chang, Flora Lau, and many, many other award-winning female filmmakers. They also live in a city where a T8 typhoon signal, which closes schools, prohibits all but essential work, and strongly discourages going outside, was in effect on Oct. 10, 2021. Wang also spoke about what it meant to her to be in Hong Kong on June 4th, a day her social media showed her shopping. Perhaps this was part of what the LA Times meant about Wang’s “ability to be both inside and outside Hong Kong’s discourse that allows her to glamorize the daily realities of locals.” It certainly does nothing to reinforce her assertion that there was “no way I'm going to represent a place like Hong Kong and not do it in Hong Kong authentically.”

The first episode contains a single shot of a street demonstration (which one must be familiar with in the first place to actually recognize, such is its subtlety), where people chant “I want real universal suffrage,” something guaranteed in Hong Kong’s Basic Law. Like the actor with the yellow umbrella in episode five, it is only the cameras that kept the chanting extras safe. They could not utter these words outside of the production in 2021. It has been illegal in Hong Kong since the passage of the National Security Law. It will likely become even more illegal under the impending Article 23. The idea of additional illegality may seem ridiculous, but we are after all talking about a judiciary that convicted a woman for assaulting a police officer with her breast.

Of the protest scenes, Wang claims it was “very important to me to be able to show this particular moment in this year in Hong Kong very accurately.” She also stated that “We shot most of the political stuff in Los Angeles, it’s definitely challenging. You know there is [sic] a lot of questions of like [sic] ‘Can you show this’, ‘What can you not’… We worked with legal teams to really guide us, because you have to do it responsibly also, and there’s so many people who are working on it, who live in Hong Kong.” By attempting to make sure the series did not offend the government that people were protesting against, Wang has explicitly chosen a side, and it is not that of the protesters. It is instead the side that now declares all protests in Hong Kong to be the result of foreign agitation and is preparing to implement Article 23, making virtually anything the government wishes a matter of national security, including film and television programs. The end credits of episode four have audio of what may at first seem like genuine protest slogans, but they are not. They may not even be actual words. One of the most common slogans heard in 2019 was “Fight for freedom, stand with Hong Kong.” But that slogan is not what we hear. Instead, it has been truncated to “Fight for Hong Kong,” something few if any protesters ever said. Even more worrisome, the phrase, intentionally or not, dovetails neatly with the retrospective official government declaration of the protests as “black violence.”

Interestingly, Expats is not currently available in Hong Kong. There have been claims that the government refused to allow it, but these claims are at present unsubstantiated. It certainly lends the series a kind of credibility it may not be entitled to. The coverage of the series’ release includes some rather unfounded assertions that it is ‘about’ 2014’s Umbrella Movement:

The Dazed headline seems to reflect an effort at some kind of relevance or substance after the fact, two things Expats sorely lacks. It should be noted that the source novel is set in 2010. The production received assistance and allowances from the Hong Kong government, happening as it did in the midst of the Covid 19 pandemic and the city’s draconian quarantine measures. During production of Expats, Nicole Kidman and four crew members were granted quarantine exceptions at a time when regular citizens of Hong Kong faced three weeks of mandatory quarantine at their own expense, as well as constant surveillance via the ‘Leave Home Safe’ app, which was required for entry into restaurants, stores, and other locations. The production crew, including the director, were seen ignoring mask mandates inside and outside of their duties.

In the first three episodes, there is no mention of the Umbrella Movement. There is no mention of anything about Hong Kong, really. But given the characters and their (self) interests, it’s an unfortunate kind of verisimilitude. Wang claims that her vision of the show was formed by “just spending a lot of time in Hong Kong itself and talking to people who have had these experiences. For me, being a filmmaker is [having] the same philosophy I carry when I travel, which is, I'm not there to change things and people; I'm there to be a fly on the wall.” In that sense, the show succeeds; it reflects and even adopts the attitudes of the monstrously self-absorbed people whose lives it chronicles. Had Expats wanted to truly reflect the reality of its characters’ lives in Hong Kong and their view of protests, it could have been accomplished by a single line of dialog bemoaning protests unforgivably impeding travel to yoga lessons, or declaring the protests unacceptable.

According to recent articles about the series, Nicole Kidman’s character finally realizes there is a world outside her bubble in the finale of the sixth and final episode. I am unsure that this ever happens, even after viewing the episode. I also don’t know why it is compelling, necessary, or important to watch a monstrously selfish person finally realize that there is an entire world outside of their bubble. A series that ostensibly is trying to honor Hong Kong reduces an existential battle for a city of seven million people to an emotional beat for a single self-absorbed person who has shown only contempt for the city and the people in it. An article in Cultured calls the show “an aching and atmospheric dive into how we carry collateral damage, and what happens when it starts to define us,” and in case we didn’t get it, the article’s title explicitly refers to the “achingly nostalgic visual language of Expats.” We are apparently expected to equate the emotional ‘ache’ of wealth-driven ennui with being shot in the face with ‘less lethal’ ammunition, which happened more than once. I refuse to indulge that kind of selfishness, whether the characters’ or the producers’. Lulu Wang claims to have “really connected to the spirit of Hong Kong and wanted to make sure that I was able to translate that and I do think that that’s what initially intrigued me about the project was the resilience of Hong Kong as a parallel to the resilience of these women.” Only in Hollywood can real-world politics and police brutality be reduced to a metaphor for personal growth of the wealthy in a fictional narrative. It’s a nauseating level of hubris, but that’s Hollywood.

Wang says Expats is “a show about people who are about to lose their home, who are about to leave their home. It's about changes: political changes, personal changes, tragedies.” If the protagonists of Expats share any common trait, it is that none of them consider Hong Kong their home. Dialog makes this explicit. Two thirds of the way through the series, no local person has been heard at all, let alone talking about losing their home, something that was occurring while the series was being filmed in Hong Kong. Wang further states that there is an “ebb and flow of how much we want to be in control. We are often the victims of circumstance, and yet we do have so many choices within our circumstances. I'm very existential like that. I believe that no matter what the cards are there are still small choices that you can make minute to minute, day to day.”

Very few people who lived in Hong Kong from 2019 forward would agree with, let alone say, such trite, dismissively banal things. Still, those sentiments are certainly better than the director’s claim that “Being on the receiving end of having been imperialized, and being from a place that has been imperialized, I'm just very aware of it and trying to make myself as small as possible.” Lulu Wang was born in 1983, so her claim to having been imperialized is odd to say the least. Perhaps she can start a production company called 21st Century of Humiliation Films.

I watched all of Expats despite the arrogant fictions it expected me to tolerate, in spite of how angry it made me. The Hong Kong government’s penchant for ‘enforced fiction’ only makes Expats that much more grating. In the last ‘election’ for Chief Executive, John Lee was the sole candidate in what the government insisted was still a democratic process. Having resurrected the colonial-era sedition law that criminalizes ‘provoking hatred of the authorities,’ criticism of the voting was muted, to say the least, aided in no small part by the erasure of all but pro-government media, an exercise accompanied by constant braying assurance that Hong Kong still had freedom of the press. The former police chief can blithely state that the police never entered the campus of CUHK, the location of a Pulitzer-prize winning photo of a protester being pursued by police. More recently, textbooks in Hong Kong have begun stating that Hong Kong was never a British colony, simply “under colonial administration” until 1997.

I could leave, but many people in Hong Kong don’t have that luxury or privilege. What Expats teaches us, if anything, is that there are many people in the world more than willing to shove known falsehoods into your face, daring you to disagree or simply disengage, and doing so from a place of unassailable power. I’ve had my fill of hubris, ignorance, and condescension from far too many people exploiting a city I once called home for their own cheap personal agendas.

I watched Expats so you don’t have to.

Don't sugar coat it. Tell us how you really feel. Actually, this is the review I want to write about 90% of the Movies and TV shows about cops or veterans.

Brilliant. Thank you.